Testing hip flexion and extension is becoming more popular. Largely because of the increase in hip arthroscopies. More research is available although it is often contradictory.

Femoroacetabular Impingement (FAI):

Casartelli et al.(2012) described decreased isokinetic (and isometric strength tested on a isokinetics machine) muscle strength of the hip flexors in patients with femoral acetabular impingement syndrome (FAI), compared with controls. However, Diamond et al. (2015) and Brunner et al. (2016) did not find a difference.

Falls:

Borges et al. 2015 showed that strength around the hip does not fall as rapidly when aging as strength around the knee (strength fell by on average 10% less in the hip).

Positioning:

These movements can be performed in either the lying, or standing positions.

The hip has the same degrees of freedom (movements) as the shoulder, however, unlike the shoulder the hip is bound tightly to the pelvic girdle making it much more stable. This stability gives the hip virtually no intrinsic motion. This limits the hips motion in each plane. This stable configuration reduces the possible contraindications and compensations (posterior tilt in flexion) are limited and easily identifiable. The bony landmarks are easy to find and the range of motion can be used without limitation as injury is unlikely.

The actions of the hip muscles are complex and often change in relation to demands. Any functional motion requires a coordinated effort by several muscles which may participate in many different actions together or individually. The function of some muscles (Medial gluteal is a good example as the posterior section rotates the hip inwards whilst the anterior section can rotate it outwards) changes depending on hip position and whether the position is weight bearing or not.

Lying position:

The supine position has obvious limitations in that the leg can not cross the hips anatomical neutral position. This means extension is tested from flexion – back to neutral – and vice versa. This obviously leaves a significant section of the range of motion not tested at all. Even adding prone testing does not resolve this problem.

Having said that it is still the position used in the majority of the literature as it offers good stabilisation and controls the effects of gravity and limb pendular forces well.

Overall the most stabilised position for testing flexion but it limits extension unless the subject can get very close to the edge of the bed. Best for flexion research poor for extension.

To view a set up video see below:

Standing position:

It is claimed that the standing position is more functional and involves the use of gravity. If the knee is allowed to flex the resulting gravitational moment of the leg is lower than if the knee was fully extended and rectus femoris contraction may result in variations of the strength curve. However, flexion of the knee is recommended, although only passively against gravity if for no other reason than to avoid sciatic nerve traction.

Mohammad (2015) has shown that testing in standing is both reliable and for men at least offers more accurate measurements of strength at higher speeds.

In the standing position (see below) stabilization is difficult if not impossible (and probably undesirable). Testing in this position is more functional than that in the seated position and allows the investigation of extension. It is claimed that this is more functional and involves the use of gravity. Best for athletes.

To view a set up video see below

Stabilisation:

Lying: In the lying position stabilisation normally only involves a pelvic strap to prevent the torso from influencing the results and a leg strap for the opposite (non tested) leg.

Standing: Stabilistion in the standing position is not normally required as this is the most functional position.

Attachments:

The thigh stabiliser pad is normally used and should be positioned just proximal to the knee joint (see below).

Axis of rotation:

The instantaneous axis of rotation is simply straight across from the greater trochanter to the axis of the dynamometer (as seen as the red line).

Anatomical zero:

With leg straight (as in standing).

Range of motion:

Unfortunately there is great discrepancy concerning the normal ROM of the hip in the saggital plane. A good example of this is Boone and Azen (1979) who found normal hip extension to be 10 degrees, whereas Dorinson and Wagner (1948) found it to be 50 degrees. The point of maximal isokinetic strength is another area of contentious debate. Callahan et al (1988), in a very comprehensive study, suggested that 45 degrees hip flexion is the point of maximum efficiency (for flexion and extension). Consequently, strength measurements should be made from 0 degrees flexion to 75 degrees flexion (and obviously back for extension).

Gravity correction:

As the lever arm can be very long and heavy in these movements setting of gravity correction is essential.

Speeds:

Debate rages on this, however, slower velocities tend to be more comfortable but higher velocities are more reliable and offer a better insight into ratios.

Dos Santos Andrade et al. (2015) found ICC for peak torque in flexion and extension ranging from 0.55 to 0.76 (high reliability) at 150º/s. These were higher than the results at 30º/s

Mohammad (2015) also found high correlations at 180º/s again these were higher than the results at 60º/s

It seems the weight of modern evidence (on a new style dynamometer) is to use higher speeds.

Hip Flexion / Extension Protocols:

Muscles involved:

Rectus femoris, psoas major, glute major and hamstrings

| Strength Test Protocols | General | Patients | Athletes | Research |

| Contraction Cycle | con/con | con/con | con/concon/ecc | con/conecc/ecc |

| Speed/s | 30 up to 180 | 30/60/90 | 30-300 | 30-500 |

| Trial Repetitions | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Repetitions | 10 | 10 | 10 | 5 |

| Sets | 3 | 3 | 4 | up to 9 |

| Rest between sets | 20-30 secs | 20-30 secs | 20-30 secs | 20 secs |

| Rest between speeds | 2 minutes | 2 minutes | 2 minutes | 2-5 minutes |

| Rest between sides | 5 minutes | 5 minutes | 5 minutes | 5 minutes |

| Feedback | nil | nil | nil | nil |

| Endurance Test Protocols | General | Patients | Athletes | Research |

| Contraction Cycle | con/con | con/con | con/concon/ecc | con/conecc/ecc |

| Speed/s | 90 | 60 | 90-300 | 90-500 |

| Trial Repetitions | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Repetitions | Max | Max | Max | Max |

| Sets | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Rest between sets | N\A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Rest between speeds | 10-15 mins | 10-15 mins | 10-15 mins | 10-30 mins |

| Rest between sides | 5 mins | 5 mins | 5 mins | 5 mins |

| Feedback | nil | nil | nil | nil |

| Strength Exercise Protocol | General | Patients | Athletes |

| Contraction Cycle | con/con | con/con | con/ecc |

| Speed/s | 30 up to 180 | 30 up to 180 | 30-300 |

| Trial Repetitions | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Repetitions | 10 | 10 | 14 |

| Sets | 6 | 6 | up to 12 |

| Rest between sets | 30-60 secs | 30-60 secs | 30 secs |

| Rest between speeds | 2 mins | 2 mins | 2 mins |

| Rest between sides | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| Feedback | bar | bar | bar |

| Endurance Exercise Protocol | General | Patients | Athletes |

| Contraction Cycle | con/con | con/con | con/con |

| Speed/s | 120-180 | 90 | 90-300 |

| Trial Repetitions | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Repetitions | Max | Max | Max |

| Sets | 1-3 | 1 | 1-3 |

| Rest between sets | 5-10 mins | N/A | 5-10 mins |

| Rest between speeds | 10-30 mins | N/A | 10-30 mins |

| Rest between sides | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| Feedback | bar/pie chart | bar/pie chart | bar/pie chart |

Notes:

Test the uninvolved or dominant limb first.

Stabilisation difficult.

Interpretation:

In the hip it is normal to look at the ratio between the right and left sides there should be a 0-10% difference between the sides. Anything beyond this would indicate a muscle imbalance which would be best corrected.

Eccentric results are generally 30% higher than concentric within the same muscle.

Concentric/concentric ratio; flexion/extension 0.60% this means the flexors are only 60% of the extensors or the other way around is the extensors are 40% stronger than the flexors

Angle of peak torque for flexion and extension is 45 degrees flexion according to Callahan et al (1988),

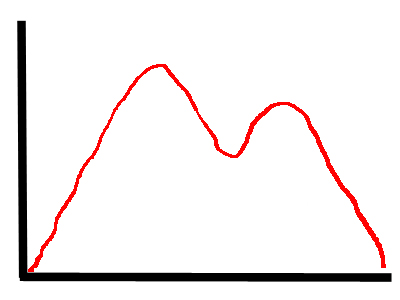

Labral Tear:

The curve will reach a peak before the point where the labrum inhibits the muscles. The inhibition is due to the pain but once beyond the range where the affected part of the labrum is stressed the torque will return giving a second peak. This M shaped curve can be biased towards the beginning or end of the curve dependent on where the damage is.

Please note absence of a curve does not necessarily indicate a normal labrum.

Concentric hip flexion shown.

Normative values:

| Smith et al. (1981) | Age | Sex | Machine | ftlbs peak | ftlbs peak |

| speed deg/s | 22-24 | m | Flexion | Extension | |

| 30 | 128.3 | 204 | |||

| 180 | 83.9 | 149.8 | |||

| Poulmedis et al. (1985) | 28 | M | |||

| 30 | 132 | 198.4 | |||

| 90 | 95.1 | 153.4 | |||

| 180 | 70.1 | 119.5 | |||

| Nicholas et al. (1989) | non trained | ||||

| 30 | 20-30 | M | 77 | 98 | |

| 30 | F | 55 | 83 | ||

| Tippett (1986) | 20 | M | |||

| 60 dominant | 105 | 200 | |||

| 60 non dominant | 118 | 191 | |||

| Alexander (1990) | M | ||||

| 180 | concentric | 145.3 | 230.1 | ||

| 180 | eccentric | 177.7 | 268.5 | ||

| 180 | concentric | F | 107 | 171.1 | |

| 180 | eccentric | 129.8 | 205 | ||

| Tippett (1986) | 20 | M | |||

| 240 dominant | 69 | 173 | |||

| 240 non dominant | 70 | 174 | |||

| Biodex Values | N/A | M | Biodex | PTBW Goal | PTBW Goal |

| 45 supine | 40-52 | 63-82 | |||

| 300 | 10-13 | 34-44 | |||

| F | |||||

| 45 | 38-50 | 57-77 | |||

| 300 | 7-9 | 28-37 |

| flexion/extension ratio % | Dominantflex/ext% | |

| Smith et al (1981) | M 24yrs | |

| 30 | 0.64 | |

| 180 | 0.59 | |

| Alexander (1990) | M 22yrs | |

| 30 concentric | 0.74 | |

| 30 eccentric | 0.75 | |

| 180 concentric | 0.59 | |

| 180 eccentric | 0.66 | |

| 30 concentric | F 20yrs | 0.79 |

| 30 eccentric | 0.74 | |

| 180 concentric | 0.65 | |

| 180 eccentric | 0.65 | |

| Poulmedis (1985) | m 28yrs | |

| 30 | 0.66 |

Hip flexor and extensor concentric strength (based on Cahalan et al 1989)

| Female | Male |

| 20-40 yrs. | 40-81 yrs. | 20-40 yrs. | 40-81 yrs. | |

| Flexion | ||||

| 30/sec | 91 | 67 | 152 | 113 |

| 90/sec | 70 | 46 | 126 | 84 |

| Extension | ||||

| 30/sec | 110 | 101 | 177 | 157 |

| 90/sec | 97 | 70 | 163 | 132 |